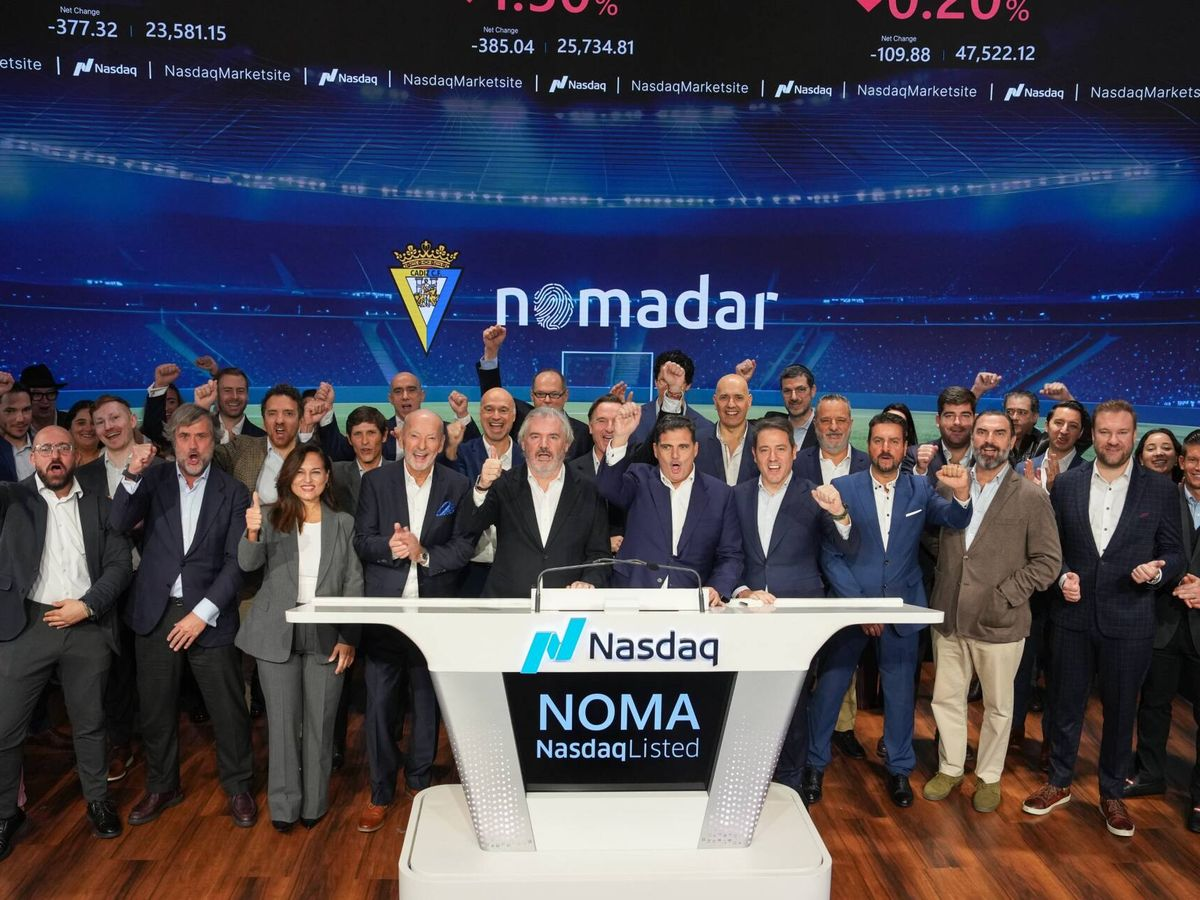

Cádiz CF has moved in a direction that very few mid-tier European clubs have attempted. Instead of relying on traditional financing through player sales, bank loans, or shareholder injections, the club has created a U.S. corporate vehicle, Nomadar Corp., and listed it on the Nasdaq in the United States. It is not a simple “sponsorship deal” or “U.S. marketing push”, it is a structural financial move with long-term consequences for governance, capital access, and the relationship between sporting performance and commercial strategy.

To understand what Cádiz is doing, you cannot look at match results. You have to understand capital markets, investment horizons, and how non-matchday infrastructure changes the business profile of a football club.

This article explains that shift.

Turning Cádiz Into a Multi-Asset Ecosystem

The core project driving this financial move is something called Sportech City. In simple terms, the club wants to build a 110,000 m² sports-anchored urban complex that goes far beyond football. The project includes:

- A large multi-use venue (≈40,000 capacity)

- Hotel and hospitality assets

- Sports science and rehabilitation clinic

- Retail and leisure areas

- Gym and training facilities

- Education and entrepreneurial spaces

The business logic is straightforward: Matchday revenue has a ceiling. Non-matchday revenue does not.

Modern football clubs are no longer just sports teams. The most financially successful clubs behave as entertainment and real estate operators where the stadium and its surrounding assets generate value every day of the year, not just when the team plays.

Cádiz wants to make that transition.

Why Go to the U.S. Market?

To fund Sportech City, Cádiz needed new capital sources. The domestic Spanish financial environment is cautious, especially for clubs whose competitive and revenue profile is volatile. Instead of relying on local lenders or selling large equity stakes to private investors, Cádiz established Nomadar Corp., a U.S. subsidiary, and pursued a direct listing on Nasdaq.

A direct listing does not raise new cash at the moment of listing, it simply allows existing shareholders to sell shares on the public market. This is important because listing ≠ money in the bank. It only creates the possibility of raising capital later — through secondary offerings, private placements, or structured capital raises.

This is a long-term capital market positioning move, not a short-term liquidity injection.

Who Controls the Project?

Despite appearing to “go public,” Cádiz has not ceded control.

The club uses a dual-class share structure, where Class B shares carry multiple votes compared to the publicly tradable Class A shares. Even if some Class A shares are sold, Cádiz retains more than 90% of total voting power.

This ensures:

- The sporting identity and decision-making remain local.

- Public investors do not dictate sporting strategy.

- The club uses capital markets without losing control.

This governance design is similar to what you see with:

- FC Bayern (ownership split but majority held by club members)

- Manchester United under Glazer family (super-voting shares)

- Many tech companies (Google, Meta) that want capital without losing strategic autonomy

Financing: Convertible Bonds With Yorkville

Before the listing, Cádiz secured €25.6 million in financing through convertible bonds from Yorkville Advisors. This financing is used to support early project phases and working capital needs before large capital inflows begin.

A convertible bond is debt that can turn into equity (shares).

But Cádiz negotiated guardrails:

- Conversion capped at around 30% of share capital (with veto above 10% conversion at any moment).

- This protects against hidden loss of control through gradual conversion.

- However, it introduces market-linked dilution risk: if the share price falls, more shares are needed to convert, increasing dilution.

The Funding Target Nobody Should Confuse With Reality

Public interviews and investor communications reference a €123 million equity target linked to the U.S. market strategy, plus ~€167 million in project debt financing, and club-level contributions spread over multiple years.

These numbers are targets, not completed raises.

- The listing enables future raises.

- It does not guarantee them.

- Success depends on investors believing in Sportech City’s long-term value creation.

This is where sporting performance still matters:

- Cádiz in LaLiga is a different business case than Cádiz in the Segunda.

- Broadcasting income directly affects wage limits and, indirectly, the credibility of the development plan.

The football remains the engine, even if the business is becoming larger than the pitch.

Commercial Model: Cádiz Wants to Monetize Knowledge, Not Only Seats

Nomadar holds a 20-year global license to commercialize Cádiz’s High-Performance Training (HPT) methodologies, with the club receiving 15% of Nomadar net sales on these activities.

This means the club wants to earn money from:

- Training centers

- International academy partnerships

- Sports science programs

- Branded coaching methods

- Potential data / analytics / performance tooling

If executed well, this creates recurring, scalable, location-agnostic revenue… something matchdays cannot provide. If poorly executed, it becomes branding without substance.

Real Risk: Timing + Execution + Market Sentiment

The project’s success rests on three pressure points:

| Pressure Point | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Permits & construction timeline | Delays increase financing cost and risk overruns |

| Club’s league status | Revenue swings between LaLiga and Segunda materially impact credibility and liquidity |

| Capital market appetite | If Nomadar shares trade thinly or remain volatile, raising new capital becomes expensive |

Conclusion

Cádiz is testing a model that mid-tier clubs around Europe are increasingly considering:

- Build infrastructure → stabilize revenue → escape survival-cycle economics.

Traditionally, only big clubs like Real Madrid, Bayern, Barça… had the balance sheet and credibility to do this. Cádiz is trying to break that pattern by bringing Wall Street into the funding model. If it works, Cádiz becomes structurally stronger than many clubs at its sporting level. Keep local control, expand global revenue, and build a club that does not live hostage to matchday results.

If it fails: the project becomes debt-heavy, diluted, and delayed, sporting performance becomes fragile, and the financial complexity becomes a liability instead of an asset.

The move is bold and intellectually coherent, a high-risk, high-reward corporate strategy applied to football.

Whether Cádiz can deliver lies not in the announcement, but in the next five years of construction decisions, capital markets appetite, and on-pitched survival.