The Dream That Can Turn Into a Nightmare

Imagine the excitement: a country wins the bid to host the FIFA World Cup. Politicians promise economic growth, new jobs, and a legacy that will last for generations. Fans celebrate, dreaming of packed stadiums, electric atmospheres, and their country being in the global spotlight. But after the final whistle blows and the last fan leaves, what happens next?

For some nations, hosting the World Cup has been a golden ticket, leading to infrastructure improvements and long-term economic benefits. For others, it has been a financial disaster, leaving behind empty stadiums, unpaid debts, and an economy struggling to recover. Let’s break down what hosting really means—beyond the glamour of the opening ceremony.

The True Cost: When Budgets Explode

When a country bids for the World Cup, the estimated costs often seem reasonable. But history has shown that cost overruns are almost inevitable, turning a planned investment into a financial black hole.

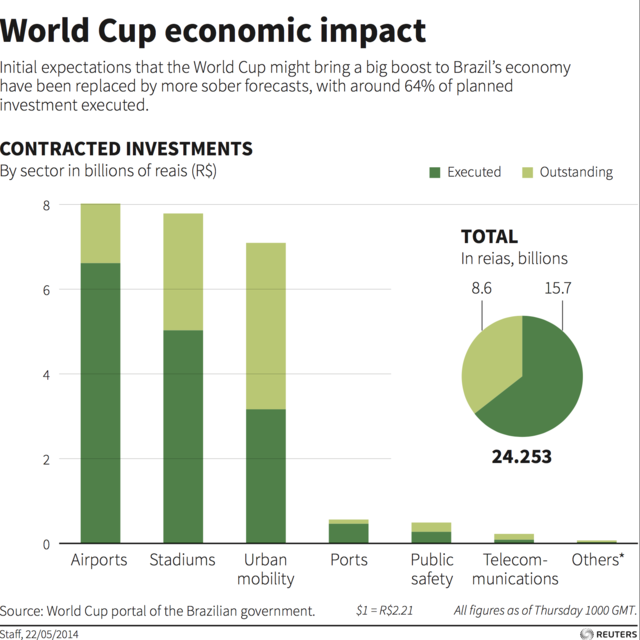

- Brazil 2014 is a perfect example of this. Initially, the government expected to spend $1 billion on stadiums and infrastructure. By the time the final tally was made, the cost had ballooned to $15 billion. The most infamous case was the Arena da Amazônia in Manaus, a stadium built in the middle of the Amazon rainforest at a cost of $270 million. The problem? There was no local football team big enough to use it, and maintenance costs were draining millions from public funds. Today, the stadium is barely used, a perfect example of a « white elephant »—a flashy but useless investment.

- Russia 2018 followed a similar pattern. The total expenditure was around $11.6 billion, making it one of the most expensive World Cups in history. While Moscow and Saint Petersburg benefited from infrastructure upgrades, smaller cities like Kaliningrad and Saransk now have stadiums that are struggling to find regular tenants.

- And then we have Qatar 2022, the most expensive World Cup ever, with an estimated cost of $220 billion. To put that in perspective, that’s more than all the previous World Cups combined. The country built seven new stadiums, a metro system, and entire cities from scratch. While Qatar’s vast oil wealth can absorb the cost, for most nations, such an investment would be economically suicidal.

Source: https://www.statista.com

Tourism Boom or Temporary Hype?

One of the biggest justifications for hosting the World Cup is the promise of a tourism boom. But does it actually happen?

- Germany 2006 is often used as a success story. The country saw a 10% increase in tourism in the years following the World Cup, and the tournament helped solidify its reputation as a major travel destination. The key? Germany was already a top tourist destination, so the World Cup acted as a boost rather than a temporary peak.

- On the other hand, South Africa 2010 did not experience the same long-term effects. The country spent $3.6 billion on infrastructure and stadiums, expecting a massive tourism boom. While the tournament itself brought around 300,000 visitors, tourism numbers dropped sharply afterward. Many of the new hotels built for the event struggled to stay profitable, and some were even abandoned.

- Brazil 2014 faced a similar issue. The government had promised increased tourism, but the high prices during the tournament actually discouraged visitors. Many tourists who would have traveled to Brazil at other times stayed away due to inflated hotel and flight costs.

FIFA, meanwhile, made $4.8 billion in revenue from Brazil 2014, taking all the profits while the host country was left to deal with the financial consequences.

Source: https://www.statista.com

Jobs and Economic Growth? A Temporary Illusion

Supporters of hosting the World Cup argue that it creates jobs and boosts the economy. But let’s take a closer look at the reality:

- The majority of jobs created are temporary construction jobs, which disappear as soon as the tournament is over. In South Africa 2010, around 130,000 jobs were created—but once the stadiums were built, most of these workers were left unemployed.

- Brazil 2014 had the same issue. The government promised a lasting economic impact, but many workers found themselves jobless just months after the event. Meanwhile, public spending on healthcare and education was cut to compensate for the World Cup budget overruns, leading to massive protests.

- Russia 2018 was a mixed case. While the government reported a $14 billion economic boost, much of it was concentrated in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. The smaller host cities did not see long-term benefits.

Source: https://www.weforum.org

White Elephant Stadiums: The Biggest Financial Trap

Perhaps the most visible reminder of a failed World Cup investment is the number of stadiums that are never used again after the tournament.

- The FNB Stadium in Johannesburg, built for the 2010 World Cup, is still in use but struggles to generate enough revenue to cover maintenance costs. Other stadiums, like those in Polokwane and Nelspruit, barely see any football matches and are now used for occasional concerts and events.

- The Estádio Nacional in Brasília, built for Brazil 2014, cost $550 million to construct and is now used as a parking lot for buses.

- Russia’s World Cup stadium in Saransk, a city with a population of just 300,000, has no major football club to use it.

Even when stadiums remain in use, they often require heavy government subsidies just to stay open. This means taxpayers continue paying for them long after the World Cup is over.

So, Is Hosting the World Cup Worth It?

The answer depends on how well a country plans for the long term. Some nations, like Germany (2006) and France (1998), successfully used existing stadiums and carefully planned infrastructure investments, ensuring long-lasting benefits. Others, like Brazil (2014), South Africa (2010), and Greece (2004 Olympics), overspent on projects that became financial burdens.

Then there’s Qatar 2022, the most expensive World Cup ever at $220 billion. Unlike past hosts, Qatar didn’t aim for direct financial returns but used the tournament to boost its global influence. Whether this strategy pays off remains to be seen, but no other country could afford such an approach.

For most countries, however, the risks are much greater. Unless there is a clear post-World Cup strategy, the tournament often leaves behind massive debt, empty stadiums, and broken promises. One thing is certain: FIFA always wins, taking billions in revenue, while the host nation is left to deal with the financial consequences. For any country considering bidding for the World Cup, the real question should be: is the glory worth the price?